‘The Last of England’ by Ford Madox Brown (1855)

Standing on the side-lines of Britain’s ongoing EU referendum debate makes for a peculiar and a rather worrying spectacle. It is probably the single most important political decision this country will make in a generation; a decision that will echo for decades and have grave economic and political consequences not only for Britain, but for the future of a continent. Yet, the voting public is presented with a string of misinformation to base this seminal decision upon that would make any propagandist blush. As the story goes: should Britain leave the union a veritable Arcadia awaits this ‘sceptred isle’ – a renaissance akin to a third British Empire where international trade links would be forged and ‘Britishness’ saved for posterity. Whilst remaining in would inexorably mean the advent of an ‘Asiatic horde’ descending upon Stevenage and Wellingborough alike, local pubs replaced by Polski skleps, chippys into döner kebab shops and the death of English as a language.

A Nation of Emigrants

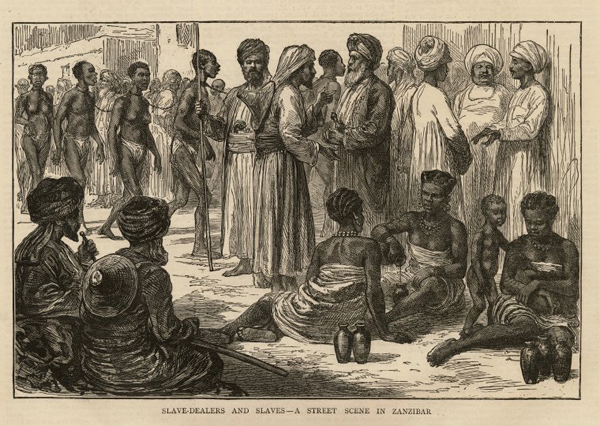

It is an odd mix of arrogant British exceptionalism combined with a fear of ‘the other’ – a familiar refrain in xenophobic political discourse from the Athenian and Roman notion of the foreign ‘barbarian’ to Australia’s ‘yellow peril’. Quite predictably then, the ‘Leave’ side base their campaign on the emotionally evocative issue of immigration, conveniently forgetting the backdrop of globalisation or indeed Britain’s centuries-long role in forging, fomenting and benefiting from this very process. Has Britain’s own waves of mass emigration in the 19th-20th centuries already been forgotten? Have the 11 million men, women and children that left these shores for the New World, the antipodean Dominions or the settler colonies in Southern, Central or Eastern Africa all been erased from Britain’s collective memory? Or is it simply overlooked that Britain, a nation of emigrants since Tudor times, maintained negative net-migration figures until the early 1980s? For anyone believing the mantra that British culture is somehow under siege, or that this slippery concept of ‘Britishness’ is on the verge of extinction in the face of mass overseas migration, then ask yourself what is the most commonly understood and spoken language in the world, who is the world’s most famous living person or what country is best known for its bad food and dry humour? I think you will find the answers are English, the Queen and Britain respectively. A simplistic line of reasoning warrants an equally simplistic retort, although it belies the hypocrisy of British anti-immigration rhetoric amid global Anglo-phone cultural dominance.

The second component to the Little Englander set of arguments pertains to sovereignty – that is, when the issue is not simply an underhand way of referring to immigration policy. In similarity with ‘Britishness’, the concept of sovereignty is an elusive one. In an ever increasingly interconnected world, the very notion of national sovereignty is becoming an anachronism. Even at the height of British imperial might, Britain depended upon a system of informal international agreements and understandings with continental powers. ‘Splendid isolation’ was never more than a caricature that even Conservative Lord Salisbury (ascribed to Salisbury despite being one of Otto von Bismarck’s closest partners) thought to be dangerous. Perhaps counter-intuitive, but in today’s global economy it is membership of a regional trading bloc that acts as the guarantor of a population’s political and economic agency, i.e. ‘national sovereignty’. Whereas societies of the early-modern world might have been usefully atomised within the confines of a nation-state, these political structures are inadequate to meet the challenges of the globalised twenty-first century – a time where environmental, political and economic concerns have little respect for national frontiers and much less can be addressed by one state in isolation. Outside these great political and economic constellations, a small or medium sized nation-state will find itself the victim of the classic imperial strategy of divide and rule, as indeed Britain, of all countries, ought to know. A British retreat from the EU would in any respect represent a Pyrrhic victory for these self-professed champions of national sovereignty. Should the United Kingdom want access to the internal market it would find itself in the unenviable position of Norway (minus the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund, an advanced welfare state and a progressive political culture). It would have to comply with all the existing EU legislation (including free movement of people) whilst renouncing any influence over policy-making. In other words Britain would choose to become an EU satellite state. Perhaps not an unacceptable proposition for a country of five million such as Norway, but for a former world power with over 60 million inhabitants it seems a peculiar, self-destructive sort of choice to make.

If Britain instead renounces this political subservience and its access to the internal market, the country would face an economic malaise, unknown both in scale and scope. Whilst a recession is a near certainty in the short-term, the longer-term prospects, indeed perhaps for several decades, would likely see Britain experiencing markedly slower economic growth than if it had remained in the free-trading zone, an income loss far outweighing the £136m weekly ‘subscription’ charge. One does not need to be an economist to understand that a tariff barrier imposed by a potentially hostile EU, eager to set an example to deter other potential leavers, would impact negatively upon the British economy (as of 2014 the United Kingdom exported 44.4% of its goods and services to the European Union). Unlike its position in the nineteenth century, contemporary Britain does not enjoy many absolute or comparative advantages over other leading economies. To retain competitiveness outside the European common market would mean the reduction of wages and a general weakening of the employment conditions of British workers. In other words, competitive advantages could only be gained through a set of beggar-thy-neighbour policies – a race to the bottom Adam Smith warned against in his Wealth of Nations. Rather than a Singapore or Hong Kong, who enjoys commercial access to their hinterlands, this post-EU Britain would likely assume the characteristics of an offshore tax-haven: a libertarian casino economy under the auspices of a ‘corporate-friendly’ night-watchman state, complete with the negative consequences that usually follows for such polities’ ordinary citizens. Little wonder then that it is the Tory hard-right who are Brexit’s staunchest proponents, manipulating the misinformed working-classes to support their cause, akin to turkeys voting for Christmas.

The European Union and the Pax Europaea

Despite what impression you might get from the Brexit-fevered British tabloid press, the European Union is not only about trade or the prosaic straight cucumber. The Union is principally a project of peace, a sharing of sovereignty to the mutual benefit of all member-states. Perhaps an obvious observation to make for any ‘continental’ of the older generation, but an argument that is at best whispered, at worst mocked on the north side of the English Channel. Viewing the history of Europe over the past two millennia, there are two periods that stands out for their relative internal stability, one is famously called the Pax Romana (27 BC to 180 AD) the other, less famously so, the Pax Europaea (1945-today). The latter achievement is largely credited to the creation of what is now the European Union and garnered the supra-national organisation a Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. There is an interesting inverted parallel between the two periods. Whilst peace within the Roman Empire was in part forged through the use or threat of military coercion from the imperial centre, what Tacitus famously observed as: ‘they create a desolation and call it peace’, its contemporary equivalent is ensured by a framework of institutions created through an unprecedented voluntary pooling of sovereignty. It is these structures, despite all their flaws and foibles, that prevents radical agency from disrupting stability and, in the long-term, acts to all member-states’ mutual benefit.

The other inverted parallel can be drawn between the population movements that eventually led to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and indeed contemporary debates over Brexit. Whilst Rome was overrun on account of its inability to vanquish or integrate the external hostile populations into its empire, a similar problem faces the EU today with regards to how it assimilates the ‘other’. Whilst Rome was perceived an imperial conqueror, the EU is surrounded by countries that are sympathetic to its cause and who want to join. This alone is testament to the EU’s perceived economic and political advantages. The challenge, therefore, is not the population movements of peoples’ per se, but individual member states’ reaction to migration. Existing member states can either view immigration as an opportunity, and rationally take heed of academic studies showing that migration has an overall positive impact on EU economies, or they can choose the emotional xenophobic response that view immigration, skilled or unskilled, as a threat. Apart from the historical analogies, there is something deeply immoral about undermining a system of international relations that maintains dialogue and co-existence over instability and war. One needn’t look further back than to the breakdown of the Concert of Europe in 1914 or the League of Nations in 1933-9 to witness their potential disastrous results.

A Distraction from Domestic Political Failings

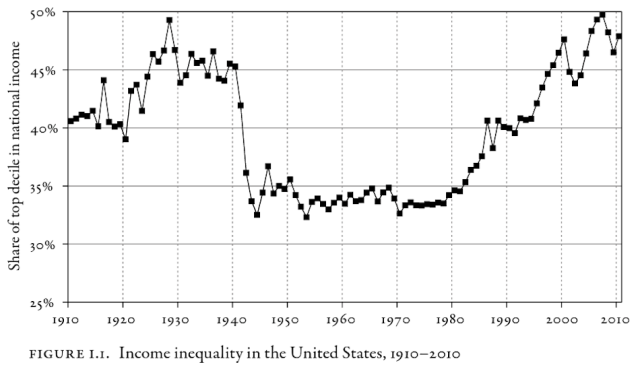

With regard to immigration it is worth noting that Britain is not a party to the Schengen Agreement and as such would not directly be affected by illegal migration within the zone of free movement. This, however, does not prevent populist politicians from invoking that old favourite of distracting the public with an external threat – in this case the EU – in order to avert the voters’ gaze from domestic political failings. The vast majority of challenges facing Britain’s population today such as housing shortages, unemployment, spending cuts and rising inequality are the result of Westminster’s neo-liberal consensus, a Conservative policy package more commonly known under the epithet of austerity. That the same home-grown Tory politicians responsible for these policies have the audacity to blame the European Union and remain largely unchallenged, is testament to a partisan British press that has failed in offering informed and reasonably objective journalism to its readers.

Regardless of the EU referendum’s outcome, the debates are from a historical point of view interesting as they offer such a clear demonstration that imperial ideologies often long outlive their empires. As Professor Danny Dorling pointed out in his excellent article, one of the main reasons behind Britain’s uneasy relationship with the EU is its imperial nostalgia. Particularly Britons of the older generation still, to a degree, perceive their society’s identity through the prism of a global empire, rather than as a medium-sized state that principally belongs within the geographical, economic and political sphere of Europe. In this way, the referendum might prove the ultimate end to the British Empire, imagined or otherwise, particularly if Scotland should seek to leave the United Kingdom following an English leave and Scottish remain vote. This said, Britain has left an important historical legacy in Europe and the wider world which would naturally be left unaffected by any result. However should Britain decide to cancel its membership it would lose not only a substantial amount of its political influence in Europe, but by extension in the Extra-European world as well. This is due to the multiplying effect of each member state’s power through working in solidarity as one great bloc, very much akin to the improved negotiating power of individual workers who organise themselves in trade unions. Hence, it is the very act of relinquishing sovereignty that ensures the nation-state’s agency in this highly globalised world – to paraphrase the late Professor Alan Milward’s thesis in ‘The European Rescue of the Nation-State‘ (1992). Isolationist Britain would, in this ‘Leave’ scenario, not only be positioned on the geographical fringe of Europe, but in a political and economic no-mans-land between the two great trading blocs of North America and Europe: ‘splendid’ isolation indeed.